By Mohamed Lamin Sillah

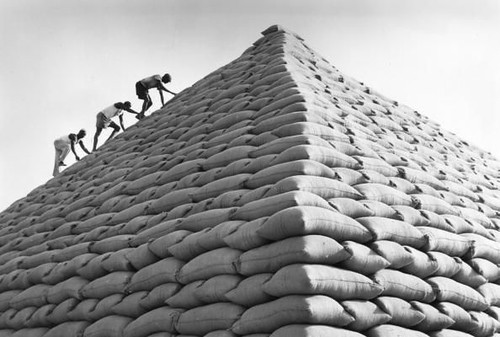

March 31st 2014 saw the official coming to an end of the Gambia’s formal groundnut marketing season. It was a season without its usual characteristics fanfare, for crowded seccos, as buying points are called here, pyramids of groundnuts, dwarfing rusty screening implements that look like mammals from prehistoric times. A season without the revelries, social ambiance and celebratory air that only flow of money can kick-start and sustain. It was a season that really never was.

Thus currently, lot of pain and disappointment is rippling through farming communities the country over. The anguish and the despair that the failure of the season brought with it contrast sharply with the glee and hilarity of the previous marketing season of 2012/2013. That season was a most dazzling success as far as the masses of groundnut cultivators in The Gambia are concerned. Prices almost doubled those of the year before, that is, the 2011/2012 marketing season and over 50% of above the minimum price officially announced. Farmers got the best prices they ever got since groundnut cultivation began in the country about 125 years ago. Some farmers got up to D20 000 for a metric ton of the nuts according to some reported cases.

Also, it was the first time in living memory that Gambian farmers were able to sell their produce at really farm-gate, nay, home-gate. The seccos became redundant and abandoned as scores of registered buyers and their agents scrambled over the nuts and rushed to the homes of farmers enticing them to sell their nuts, raising the stakes, instead of waiting for them at the designated buying points.

It was like an oil bonanza of a different type for Gambia’s mainly deprived rural communities. Not the one promised by the country’s crackpot president in June of 2004. Not petroleum oil but agro oils.

Just several years ago, before 2008, selling Gambian groundnuts was proving more difficult than cultivating them. For almost a decade, between 1999 and 2008 groundnuts produced in The Gambia carried what looked like a pariah stamp in the international market of agro-oils and nobody of substance wanted them. This was not because of any decline in world demand for the nuts or its oil and cake. No, it was, I think September 1999, if my memory serves me right. Gambian President Jammeh ordered an armed band of both uniformed and un/uniformed thugs stormed thugs, led by the late Baba Jobe, then leader of the unruly July 22nd Movement, to storm the offices of the biggest foreign investor in the country, the Swiss owned Alimenta S.A. grabbed the British CEO of the company, Richard Kettlewell, and to send him out of the country with the earliest flight out. A day after this, government announced it has repossessed the groundnut processing that Alimenta had bought when the previous government privatized it about 6 years earlier. The Gambian government stated that the privatization that saw the selling of the assets to Alimenta by the previous government was not properly done and that Alimenta w was s engaged in “money laundering.”

Alimenta dismissed the accusation and took matter up for international arbitration. Part of huge Nestle multinational company, Alimenta was no small fry in the world of ago-oils. The company’s chief executives felt they were not to chicken out in the face of the errant despot of an impoverished mini-state like The Gambia.

The Swiss company took the matter up for international arbitration in London. At the end, the government of The Gambia lost naturally. A relatively heavy fine was imposed on it. Government was however too broke to meet the fine. In fact by the third quarter of 1999, government was so broke it was printing out bank notes under the cover of introducing a new Dlike 100-note. At about the same time government introduced the Pre-Shipment Inspection Program beating the death knell of the lucrative re-export trade and scaring away a big chunk of the business class.

Getting the fine of US$11 million (not that sure of exact figure) paid was, however, no easy matte. The Government of The Gambia was, and still is, none other Yahya Jammeh, privately and personally. And since like many, if not most, of his countrymen, detest paying fines of any kind so passionately, unless held very firmly by the throat and squeezed.

The squeeze this time came in the form of an undeclared but very effective embargo against the purchasing of Gambian groundnuts by major players of the world’s oil seeds and agro oil market as a punitive measure in solidarity with their peer, Alimenta. The country’s major foreign currency earner became stranded, leaving the farmers to battle the stress caused by lack of cash. The Gambia government also found itself in a state of shock and resorted to making panicky decisions.

Such a situation is conducive environment for the coming out of all that is bad in a free liberal trade. They flew in from all the corners of the world – England, India and even Libya – and were aided by those who were home-bred. The entry of the swindlers was facilitated by the frustration of government leaders and the desperation of cultivators whose crops could not be exchanged for raw cash they need to get themselves out of their miserable existence.

In the days of the First Republic, when there was an appreciable semblance of democratic dispensation, when, on top of that, decision makers in cabinet were elected and not selected like now. Due to their sheer numerical size – a valuable asset that cannot be ignored – groundnut cultivators carried significant political weight. It was widely believed at the time that “though the oil content of Gambian groundnuts was low its political content was rather high.” This reality forced policymakers to listen to the farmers and pretended to be paying heed to their aspirations.

This however is no longer the case, as farmers remain the biggest political losers of the July 22nd Military Takeover, a day wiped out the Gambia’s democratic, political and human rights gains. It must be understood that it was not all losses for the agrarian world of The Gambia. The post junta era saw little improvement to access to schools, running water and better road networks. There was significant increase in income poverty, shortages of medicines in clinics and schools, poorer educational quality, accelerated hardship for the overwhelming majority of Gambian.

Yes, we were at a point when there was this big intrusion of groundnut traders from outside the country Generally, they came empty handed, though Agro Oils – an Indian trading set-up – came with an old processing plant it had ripped off from somewhere in Nigeria. Tulor Oil also might have come in with a plant of semi-industrial scale. The Libyans, sent presumably by the late Muammar Quadaffi, also came with plenty of cash but without any machinery. Later, some members of the late Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha also flooded the Gambian market, camping under the umbrella of GAMCO that was aided by a big powerful local business magnate who also turned out to be a Jammeh bed-fellow and front-man. But the great majority of the hustlers came without any cash that would raise any eye brow. They simply came to grab and go. There were also Gambians, many of who degenerated from the now-extinct groundnut traders’ class of former times, who also joined the fray. They also came empty-handed but armed with leased title deeds.

But the trade in groundnuts is not like the trade in wild tea or bush herbs. With groundnut you need to have a storage space, cleaned fumigated, chemical dust before starting to buy the nuts. Buyers must also be equipped with screening tools to make sure they don’t end up buying chaff instead of nuts. They need to have empty bags for farmers to export nuts, possess large scale weighing machine capable of handling up to 80 kilos, make arrangement for lorries to collect and evacuate nits and most importantly, there must be workers employed for clerical and manual jobs. Buyers must also be ready to pay commission to agents. So, it involves costs that call for pre-financing which the crowds of traders that swarmed the Gambian groundnut marketing seasons between 2000 to 2007 did not have. They were let to access compliant commercial banks like Trust Bank Ltd only through government arm-twisting and guaranty.

Another thing that the motley crows of groundnut traders depended on was that groundnut cultivators – most of who were without any other means of cash income – would be ready to part with their produce without cash down payment, with promissory notes without any due date, only Inshaalla! But since the will of God can go either way, a friend of mine back at home told me last year that was from 2003, making it ten years old.

But the farmers were on the weaker side of the bargain. They had whole compounds to feed; it was their only source of cash in come in twelve months: keeping the nuts incurred weight loss, then there was the risk of crop infestation unless they are treated with chemicals; but chemicals cost cash and cash is the question, damn it! So all throughout these periods, between 2000 and 2010, when the trade season arrived, the Gambian groundnut farmer felt like being held at ransom. They were left no choice other than “Let me have your nut on credit or let it rot.” Credit buying therefore became the once lucrative enterprise’s trademark.

The peasant masses of groundnut cultivators in The Gambia, this way, became the major victims of the Allimenta-inspired unarticulated embargo against the Gambian groundnut. Its cultivation provides means of livelihood to up to seventy percent of Gambians; it is the country’s main foreign currency earner and a pillar of the nation’s food security.

The crisis in the groundnut sub-sector forced many farmers to divert into other crops while a section of them decamped to go join the swelling masses of the poor and the unemployed in the urban and peri-urban centers. Agriculture slumped and harvested tonnages of the nut went down to never-before-known lows. The purchased tonnage of the then sole buyer, GGC [Gambia Groundnut Corporation] was a small and paltry that not more than 7,000 metric tons in 2006 and in the following year, 2007 it went down further to half that amount. It was now obvious that groundnut cultivation has stranded in the Gambia and that the system needed a good revamp.

Development partners, particularly the European Union development aid program began to realize that the embargo by Big Boys in the world of agro oils was in fact hitting the wrong person so they decided on intervening with a host of conditionalities, including handing over the management of the marketing of groundnut to an “inter-professional association of stakeholders.” This culminated in the privatization of the GGC.

In return the EU pledged to help the government of the Gambia settle its debt to Alimenta, to revamp the sector by, among other things fund the setting up of such an association and funding the repair and renovation of the GGC’s fleet of river barges and tug boats that were all in acute stages of disrepair. The EU also decided to fund a consultancy for a study of how best to go about revitalizing the Gambian groundnut sub-sector.

But as usual, the government of the Gambia, which no doubt means President Yahya Jammeh, was doing the exact opposite of what he was saying with the hope that the ‘dumb toubabs’ would not understand. In feigning commitment and compliance, the government asked the World Bank to help fund the setting up of a divestiture agency and gave a local consultant the task of preparing the GGC for an eventual privatization. It also did not openly hinder the formation of the inter-professional association the agreement called for.

But parallel with those measures Jammeh had a business associate tasked with launching GAMCO in partnership with some members of the Abacha clan in 2004. They were the first in line as buyers for any privatization. GAMCO went into high gears even before the actual privatization was launched. This was evidenced by the secret shipment and commissioning of GAMCO plant equipment from Northern Nigeria to the GCC year near Denton Bridge. It was like the natural inheritor positioning himself for a takeover. The EU representative in Banjul naturally cried foul forcing GMCO to go on a retreat. When 0ther report of a local consultant on the way forward for the groundnut sub-sector was being reviewed at the Kairaba Hotel, the consultant, himself a former cabinet minister in the Jammeh administration, was picked up by agents of the most feared National Intelligence Agency for questioning and shaking down. The same went for the chief executive officers of the newly formed inter-professional association and those of the National Authorizing Office- Support Unit. These bodies were mandated to become the liaison between the government and the EU.

To be continued

Ends

Ba Buwa is a great man! I first heard his name when I was in Kiang Karantaba Primary School between…

Honestly, everything you said here was true and valid. He is obviously my inspiration and motivation. He is my Dad.

Wishing the President and his team the best of luck , integrity and humble dedications to move the Country forward.…

Fulani can't have originated from Mandinkas, it is what Nigerians Call The ones you call Fula in Gambia

Creole is a language spoken by Sierra Leone people